Sudoku solver

If you haven’t been following along with Rubicon’s development, I can’t really blame you: it’s been an on-again-off-again affair for a few years now and the way to “follow along” has been to monitor a git repo. I may have some time for explaining at some later date, but for right now, let’s take a side-track into some functional programming in C++, and solve a sudoku or two.

I guess you know what a sudoku looks like: a nine-by-nine square grid of numbers between 1 and 9, inclusive, divided into cells of three-by-three, rows and columns. No cell, row or column may contain more than one of each number, and you’re usually provided with a subset of the numbers in the final puzzle – the fewer of those you get, the harder the puzzle is. We’ll call this the Field.

We can represent a field as an array of 81 integers. The function to solve the field therefore takes an array of 81 integers as input and outputs another array of 81 integers that is solved (if possible).

In C++, it is generally easier to represent an array that we want to pass around as a struct containing an array, so that’s what we’ll do here as well. Hence, this will look a bit like:

struct Field

{

int values[81];

};Any position in the field can have one of nine values, which can be known or unknown. If unknown, the position has up to nine candidate values (1 through 9), in a “superposition” of those values, which we can represent as an array of nine booleans. When solved, only one of those booleans will remain as true:

struct Position

{

bool candidates[9];

};That means we can also represent the Field as:

struct Field

{

Position values[81];

};This is where C++ shines: we can template the Field struct according to the type of the individual values to distinguish the two types, while retaining the same, descriptive, name:

template < typename T >

struct Field

{

T values[81];

};In Field< int >, a value can be 0 if unknown, which we’ll translate to { true, true, true, true, true, true, true, true, true } in Field< Position >. Thus, translating from Field< int > to Field< Position > is a straight-forward mapping function:

Field< Position > convert(Field< int > const &field)

{

Field< Position > retval;

transform(

begin(field.values)

, end(field.values)

, begin(retval.values)

, [](int value){

Position position;

assert(value <= 9);

switch (value)

{

case 0 :

{

bool const candidates[] = { true, true, true, true, true, true, true, true, true };

copy(begin(candidates), end(candidates), begin(position.candidates));

break;

}

default :

bool const candidates[] = { false, false, false, false, false, false, false, false, false };

copy(begin(candidates), end(candidates), begin(position.candidates));

position.candidates[value - 1] = true;

break;

}

return position;

}

);

return retval;

}Note that C++ doesn’t allow assigning a literal array directly to an array-type variable, so we have to initialize a local variable candidates with the value and copy it on.

Translating the other way around is straight-forward as well, and gives us a chance to use C++’s overloading by type: we’ll call the function convert, just like we did for the other way around, and have it call another function convert, to convert individual positions to their final value.

int convert(Position position)

{

if (count(begin(position.candidates), end(position.candidates), true) == 1)

{

return distance(begin(position.candidates), find(begin(position.candidates), end(position.candidates), true)) + 1;

}

else

{

return 0;

}

}

Field< int > convert(Field< Position > const &field)

{

Field< int > retval;

transform(

begin(field.values)

, end(field.values)

, begin(retval.values)

, [](Position position){ return convert(position); }

);

return retval;

}As you can see, we use the standard transform function from the STL to iterate through the values in the input field, convert each of them to their final value (or 0 if there’s more than one candidate), and output the result into the return value.

A note on the style

I said we’d be doing some functional programming. Functional programming is a paradigm in which functions do not have side effects: they take parameters as their input and, based only on those parametets and nothing else determine the output. This allows for a style in which you don’t have to wonder about what the state of your progam is to understand what’s going on. This is very useful in multi-threaded programming because you can get rid of most places in the program where threads need to synchronize, which in turn gets rid of deadlocks, race conditions, and a large number of other types of problems.

It may not be obvious to a casual reader how the functions and types we’ve got so far constitue functional programming in any meaningful way, but C++ is not a pure functional programming language. In Haskell, which is a pure functional programming language, these functions would have looked different, but would essentially have done the same thing: the Field type would essentially be a list of values (either positions or integers) and the convert function, which would be defined as convert :: a -> b would map between the two by doing a “fold” of some kind.

I don’t intend to push a full-blown pure functional implementation of a sudoku solver in C++ here, implementing the whole thing without local variables and using pure functional programming in a non-pure language like C++: my intent is to use a functional style in which a function does what it does with its parameters, and without producing side-effects, but is still allowed to have local variables and loops so we don’t have to rely on recursion for everything.

Addressing rows, columns and cells

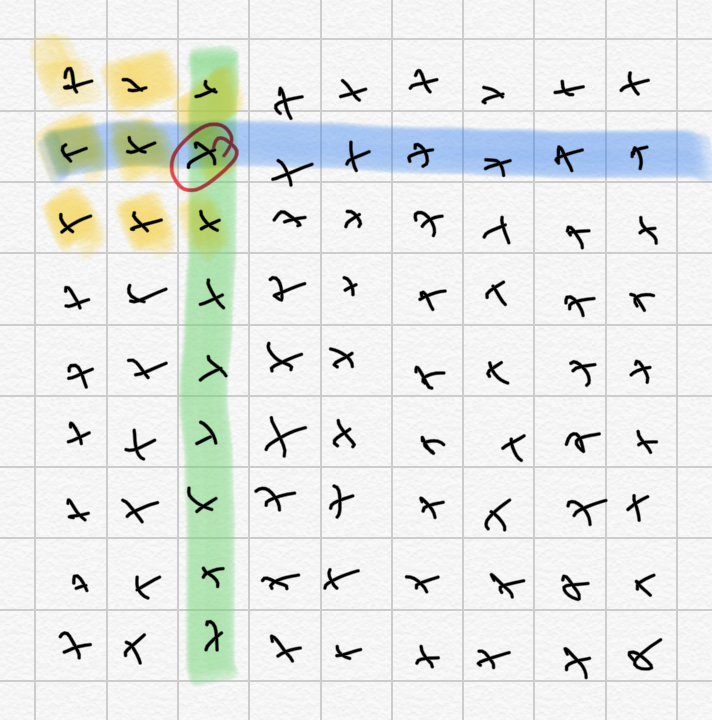

To solve any position in the field, we need to know all the values in the same row, the same column, and the same cell.

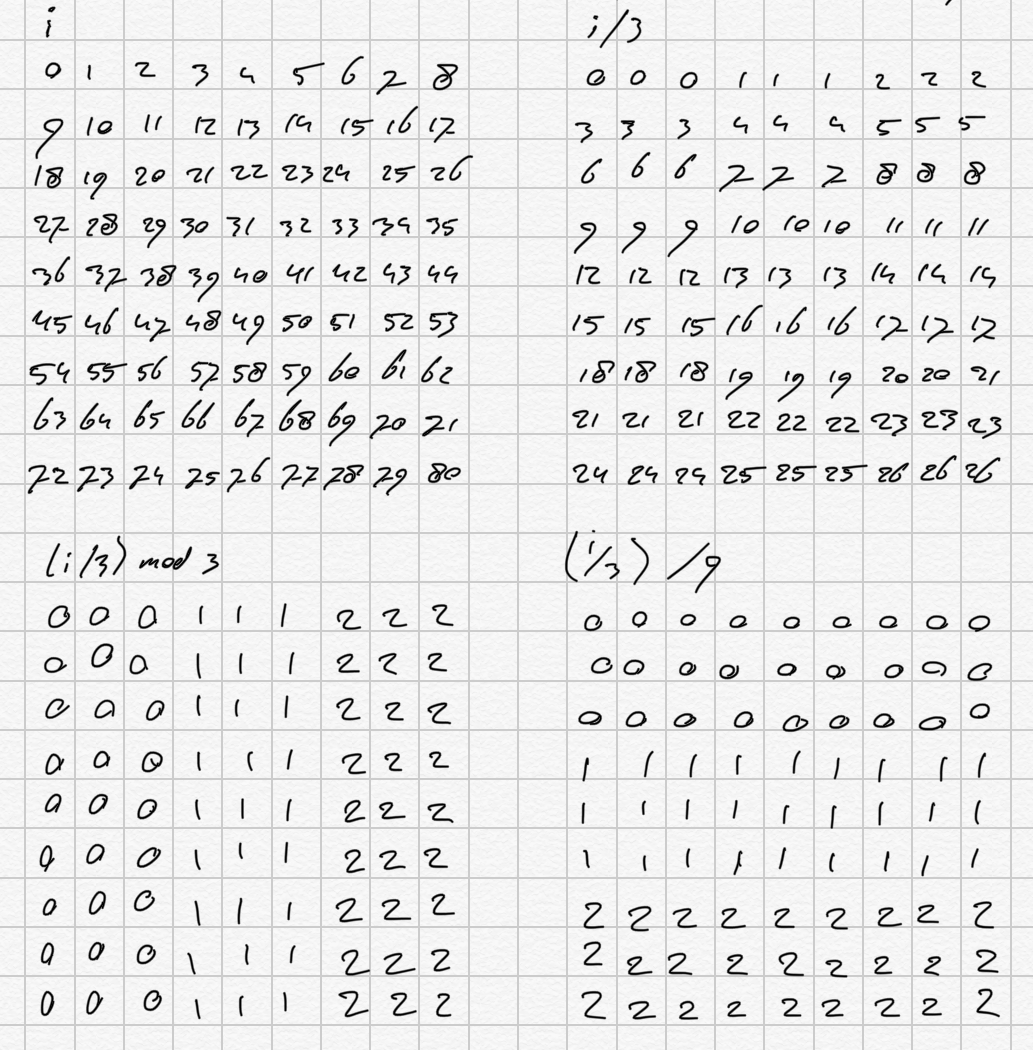

From the perspective of our array of values, a row is simply indices [0,9), [9,18), etc.ˆ1

A column consists of all indices mod 9 (so for any value, any other value that has the same index mod 9 is in the same column.

A cell is somewhat more complicated to identify:

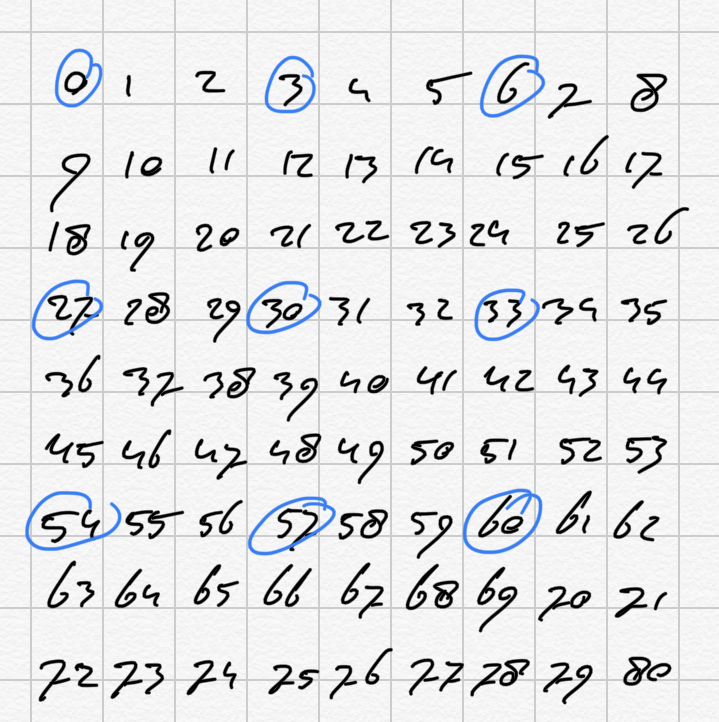

For a position P_i, every other position P_j is in the same cell if (i / 3) % 3 == (j / 3) % 3 and i / 27 == j / 27.

We can translate all of this to code as follows:

bool sameRow(int lhs, int rhs)

{

return ((lhs / 9) == (rhs / 9));

}

bool sameColumn(int lhs, int rhs)

{

return ((lhs % 9) == (rhs % 9));

}

bool sameCell(int lhs, int rhs)

{

return ((lhs / 3) % 3) == ((rhs / 3) % 3)

&& (lhs / 27) == (rhs / 27)

;

}We can find any position in the same row, column or cell as follows:

// return all indices in the same row as index, excluding index itself

vector< int > getRow(int const index)

{

int curr_index((index / 9) * 9);

vector< int > retval(9);

generate(retval.begin(), retval.end(), [&](){ return curr_index++; });

retval.erase(retval.begin() + (index % 9));

assert(retval.size() == 8);

return retval;

}

// return all indices in the same column as index, excluding index itself

vector< int > getColumn(int const index)

{

int curr_index(index % 9);

vector< int > retval(9);

generate(retval.begin(), retval.end(), [&](){ int retval(curr_index); curr_index += 9; return retval; });

retval.erase(retval.begin() + (index / 9));

assert(retval.size() == 8);

return retval;

}

// return all indices in the same cell as index, excluding index itself

vector< int > getCell(int const index, bool include_seed = false)

{

// we'll brute-force it

vector< int > retval;

for (int i(0); i < 81; ++i)

{

if ((include_seed || (i != index)) && (((i / 3) % 3) == ((index / 3) % 3)) && ((i / 27) == (index / 27)))

{

retval.push_back(i);

}

else

{ /* not this one */ }

}

assert(retval.size() == (include_seed ? 9 : 8));

return retval;

}Hence, we now have a function to transform Field< int > to Field< Position >, and a function to find all other positions in the same two, column or cell. We can now solve for a position by eliminating from the candidates any value that has already been assigned to another field in the same row, column or cell. That is not enough to solve a sudoku, but it goes a long way.

Once this function has stopped making progress, we can check each cell to see if there’s more than one candidate for a given value. If there is only one, we “promote” the position in question to that value by removing other candidate values from it. To do this, the function is fairly straight-forward: we already have a function to get all the indices in the same cell, and we know the indices of the upper-left corner of every cell:

So for each cell we can find the candidates for each number. If there is only one, it must be that number (in which case we preomote it if it didn’t already know).

Once this function has stopped making progress, we need to check whether there are candidates we can eliminate from the rows and columns. We can eliminate candidates whenever we see the “all candidates for value x in a single cell are in the same row or column” pattern. So, for each value x, we will do that check and, if it succeeds, remove all other candidate, values are in the same row.

To do this, we select the cells the same way as we did before. From each cell, for each value:

- select all candidates for the value

- check if they’re all in the same row, column

- if so: a. find all indices of the row or column in the field b. remove from that list the ones in our cell, and then c. for each remaining item in the list, remove the candidates of the value

With this algorithm in place, we can solve the vast majority of sudoku puzzles. There are other strategies we can employ, however:

- if the only candidates for a given value on a given row or column are all in the same cell, the value must be on that row or column in that cell. This means we check for such candidates per row and column.

- If N positions in the same row, column or cell hold the same N candidate values, all other positions in that row, column or cell can be stripped of those values.

Check out the code and try to add some of these yourself!