A note on the expressiveness of code

Code should clearly express intent.

I could leave it that, and probably would, if coding standards and coding styles were not such controversial subjects: whenever you wade into this subject, it seems can’t help but be swept away by a torrent of religious debate over Hungarian notation (a clearly evil phenomenon) and other such nonsense.

I generally don’t care much about UpperCamelCase vs. lowerCamelCase vs. snake_style debates – as long as you’re consistent with existing code, do whatever you find easiest to read – but I do care about two things: how things are named and, more generally, how intent is expressed in code.

As part of the project, I want to highlight a few things, including how writing expressive code can help avoid common bugs such as buffer overruns, undetected internal inconsistencies in input data, etc.

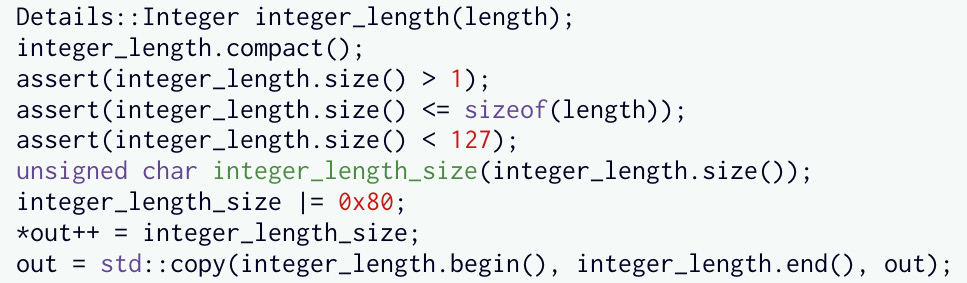

One example of expressive code can be found in the DER encoder, where the length of the TLV is encoded as a variable-sized integer.

In this code, the Details::Integer class encapsulates a particular caveat of DER encoding, in that for unsigned integers the nine leading bits of the encoded integer may never be zero. Similarly, the nine leading bits of a signed integer may neither be all zeroes nor all ones. The Details::Integer class uses the C++ type system to know whether a given integer is signed or unsigned and implements both behaviours accordingly. Most of this is hidden from view from its user, but according to the philosophy that you neither pay for what you don’t use, not suffer from unexpected implicit side-effects, the Details::Integer class has a compact method that is explicitly called to trigger this behaviour. An alternative would have been to call compact whenever begin is called, but that would have added an unexpected side-effect to begin in that this method is expected to be an accessor, not a mutator.

Also note the various assertions made by the code. If at this point in the code any of these assertions fail, something is seriously wrong: the value of the length variable, from which our Details::Integer is constructed, has been determined to be greater than 127, so it will need at least one byte to be encoded. The maximum size that can be encoded in the length field (of the length field) is 127 octets, or 1,016 bits. That can encode an integer value up to \(2^{1016}-1\). This is well beyond what can reasonably be expected to be the maximum value of a length field, which we should be able to encode in no more octets the size of the length value being encoded.

These assertions add to the expressiveness of the code by making it clear that certain things are clearly not expected at this point. It also makes clear that the encoded size of the length is expected to remain less than or equal to the unencoded size the length – i.e. the overhead of encoding the length should be negative (or no more than one byte in the case of a length of \(2^{56}=72,057,594,037,927,900\) octets or more).

Finally, note that while we do copy the integer to the output, we do so using std::copy. There are two reasons for this: firstly, it’s much clearer to read “copy the integer the output” when you read out = std::copy(integer_length.begin(), integer_length.end(), out); than when you read for (auto curr(integer_length.begin()); curr != integer_length.end(); ) { *out++ = *curr++; }; and secondly the standard algorithm implementation may know about optimisations that explicitly writing the loop may never know.

So, expressive code not only leads to fewer bugs and easier-to-maintain code, but may actually lead to more efficient code as well.